Popular Titles

Our Values

No dead levels

We build exciting games with no tedious admin phases.

Make stories happen

We help people create stories that everyone wants to talk about.

Built to last

We make bulletproof books and systems that can live forever.

Get stuff made

Everything we promise, we deliver.

Everyone gets paid

We pay and credit everyone who works on our products, and we expect to be paid and credited for our work.

Games for justice

We use our influence and power to promote justice and inclusivity, in our art and in the way we do business.

about Us

Rowan, Rook and Decard was founded in 2017 by independent game designers Grant Howitt and Chris Taylor, with Maz Hamilton as business director. We’re a growing indie tabletop studio: the creators and publishers of Heart, Spire, Honey Heist, Unbound, Goblin Quest, and many other tabletop games. This site is our storefront where we sell our games, and share resources and advice for players, as well as news and reviews of interesting games and our own projects and products.

Sporadically updated news

-

Guest Post: Plastic Bastards Saved My Life

Posted on

by

-

Illustrating Dagger In The Heart

Posted on

by

-

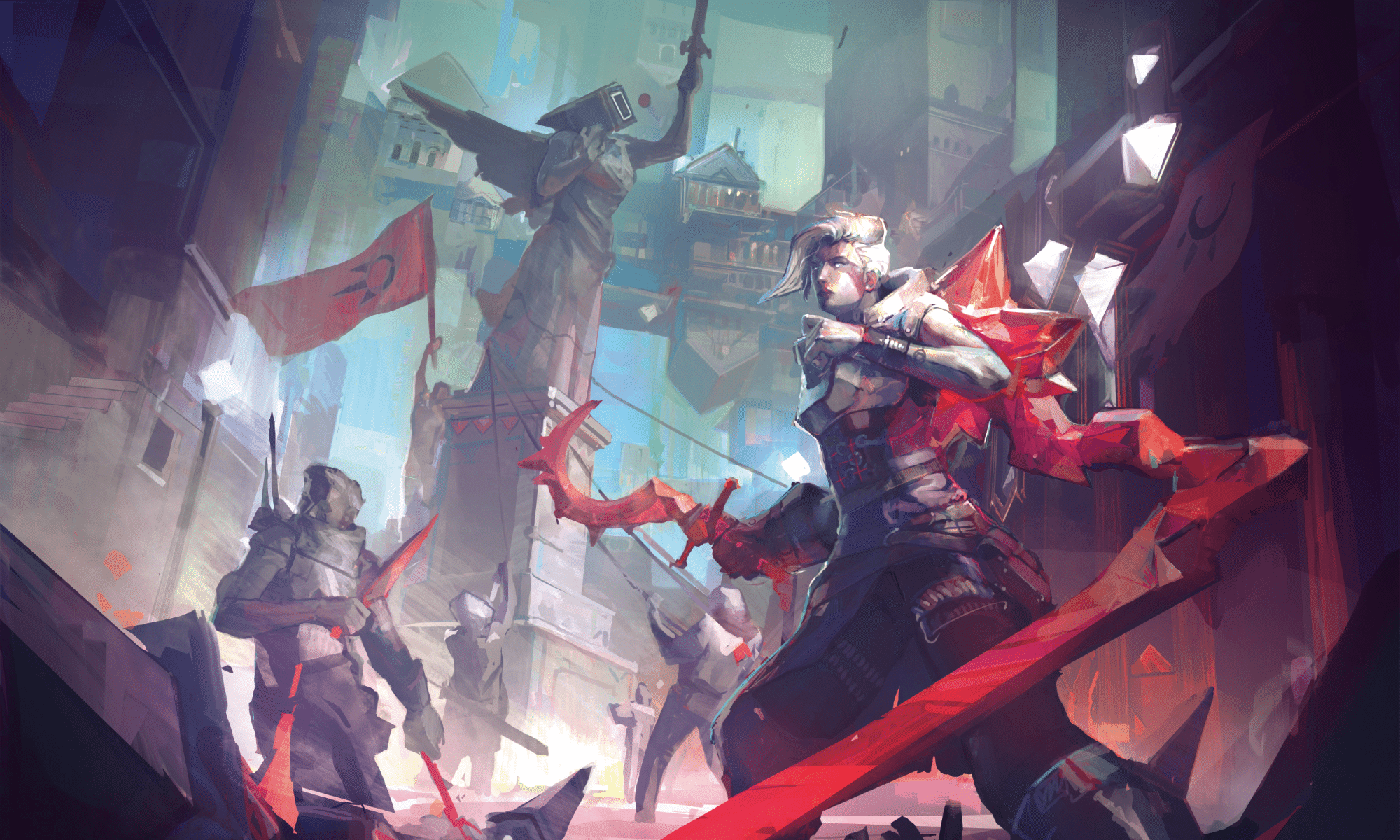

DIE RPG: It’s practically perfect (now)

Posted on

by